Pondering the Mystery

Marlene’s Musings

January 9, 2016

Eric Stokes

Music is for the people.

For all of us,

the dumb, the deaf, the dog & jays, handclappers,

dancing moon watchers,

brainy puzzlers, abstracted whistlers,

finger-snapping time keepers,

crazy, weak, hurt, weedkeepers, the strays.

The land of music is everyone’s nation – her tune,

his beat, your drum,

one song, one vote.

-Eric Stokes

I love that poem. Music is everywhere for everyone. As I lie here with my leg aloft to heal my fused ankle, I have the luxury of time to ponder things like: “Where does music come from? Is it unique to our planet? Or, perhaps, is it part of the vast universe?”

Music emerges in extreme complexity from birds, it communicates messages from a pack of wolves or the surly cat, it roars loudly in rushing rapids, its complex rhythms are in the rain, in our heartbeats. It is in the vibrations of the earth – of course. We would know nothing about music if we hadn’t heard it there first, but how did humans ever figure out how to create the written language of music and further, how does the composer lift our emotions to the surface with just a few notes? How does a composer describe a country, a river, a thunderstorm, heartache, a party, or a whole culture of people?

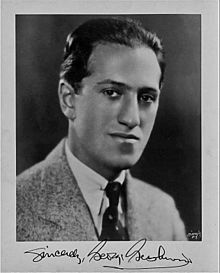

We are doing Gershwin, An American in Paris for our February cycle (click here for our concert schedule). Gershwin figured out how to musically describe who we are as Americans. I asked my daughter, “What does it mean to be an American?” She replied, “to be free, to be independent and to get to do what you want and say what you want… as long as you don’t hurt anyone else. To have a dream for yourself.” Does Gershwin’s music describe that? I think so. But how?

Gershwin’s parents were émigrés. As a young boy, George took piano lessons from Mr. Hambitzer, a musician who believed that any music that was any good had to come from European composers. So, young George practiced his Bach two part inventions and Mozart sonatas and play them for Mr. Bitzner every week. Sometimes, after playing his Mozart, George would say, “Hey, Mr. Bitzner, Listen to this, I wrote it this week. Isn’t it cool!!” Mr. Bitzner had absolutely no patience for that kind of music. In fact, he wrote a letter to George’s parents saying, “Your son is very talented but he keeps wanting to play this jazz stuff, this schlock. I simply will not allow it.”

George had the courage to continue to compose the music he heard in his head – music that was rooted in American soil – Native American chant and dance, African American gospel, spiritual and jazz. Jazz music is the ultimate in freedom – you play a tune and then you improvise something based on the tune – you get to do what you want as long as you keep the basic harmony and rhythm in tact. The immigrants who came here seeking freedom were surely improvisers – they had to create things for themselves out of basic surroundings. They were risk takers and perhaps a little wild – necessary character traits to chart such a perilous journey. Americans recognized themselves in Gershwin’s music and he became a household name.

But the mystery! How is it that when we hear George Gershwin’s music we recognize ourselves in it? 12 different notes put together in such a way as to describe us? Is it the dominant chords that are prevalent throughout that include both the perfect and the flat fifth? Is it the swinging eighths? Is it the 25 key changes that suggest extreme flexibility?

Perhaps after three months of keeping my leg up I’ll be closer to some kind of answer – or not.

It’s enough to ponder.